Thousands of people know the statue of Queen Anne, which has gazed unblinkingly over Kingston Market Place for the past 307 years.

But how many of us are familiar with another royal statue that keeps the Market Place under constant surveillance?

It depicts Edward III and is there – high on the mock-Tudor frontage of what is now the Jack Wills store – because of the King’s close links with Kingston.

For instance, he changed the name of Kingston to Kingston-upon-Thames (the hyphens disappeared in 1965) to distinguish it from another important town of the same name, which he called Kingston-upon-Hull, more commonly known as Hull.

He came to Kingston several times, and one of his first acts as king was to grant his grasping mother the annual rent from the borough for the rest of her life.

He also had a daughter, Joanna, who married a wealthy Kingston lawyer and is buried with her husband in in Kingston parish church.

And he played a key role in the creation of Kingston’s unique medieval building, the Lovekyn chantry chapel, which contains two head carvings of him and his Queen, Phillipa.

These, and many other facts concerning the king, have long been familiar to me.

However, what I failed to realise was, at national level, he was one of the finest monarchs in English history, described by some as a “perfect king”.

But I know that now thanks to Richard Barber, and his brilliantly researched new book, Edward III and the Triumph of England (Allen Lane, £30).

Edward was only 14 when he came to the throne, following the dethronement and brutal murder of his father, Edward II in 1327.

The villains behind this coup were his mother Queen Isabella (said to be the most beautiful woman in Europe) and her lover Roger Mortimer – and the pair assumed they would be able to impose their will on the new boy king.

And so they did, for a time.

Then Edward’s increasing anger at the shameless conduct of his mother and her lover, and his knowledge of what had happened to his father, led in 1330 to exile under guard for Isabella until her death 28 years later, and the execution of Mortimer on “the common gallows of thieves” at Tyburn.

From then on, Edward ruled as his own man, and Richard Barber describes in engrossing detail how he became one of the greatest warrior kings of all time, and how the destruction of the French army at Crecy in 1346, and the siege and capture of Calais that followed, marked a new era in European history.

For, to quote the book’s jacket, “France, the most powerful, glamorous and respected of all western monarchies, had been completely humiliated by England, a country long viewed as a chaotic backwater,or a mere French satellite”.

As Edward reigned for 50 years, and this book has 649 pages, one can only give a tiny taste of his achievements and adventures here.

So it is suffice to say his stable, sometimes inspirational, leadership gave England a new order and stability, while his passion for chivalry led to his creation of the Company (later the Order) of the Garter for his most gallant companions.

This, and the chivalric pageantry of the English monarchy, endures today as two of his several lasting contributions to English history.

Edward’s years of glory gave way to misery in his declining years.

His much-loved wife Philippa, and three of their daughter, predeceased him.

So did his brilliant warrior son, the famous “Black Prince”, who died from an unknown illness in 1376.

Edward himself died a year later.

He was succeeded by his 10-year-old grandson, Richard II, who is said to have been staying in Kingston when he got the news of his accession.

Richard’s unsteady reign ended 22 years later when, like his great-grandfather, Edward II, he was deposed and murdered.

One of the few blots on Edward III’s personal life is his affair with the notorious Alice Perrers, one of his wife’s attendants.

Richard Barber calls her “ambitious, and a shrewd businesswoman, who was determined to use her charms on the elderly king, and to make her fortune”, adding “it was not until after Philippa’s death in 1869 that she played a major part at court.

“But her activities in the last years of Edward III’s reign were to be remembered, and were to give him a lascivious reputation at odds with that of his prime.”

One result of this illicit union was the birth of a daughter, Joanna, who married a prominent Kingston lawyer called Robert Skerne (after whom Skerne Road is named).

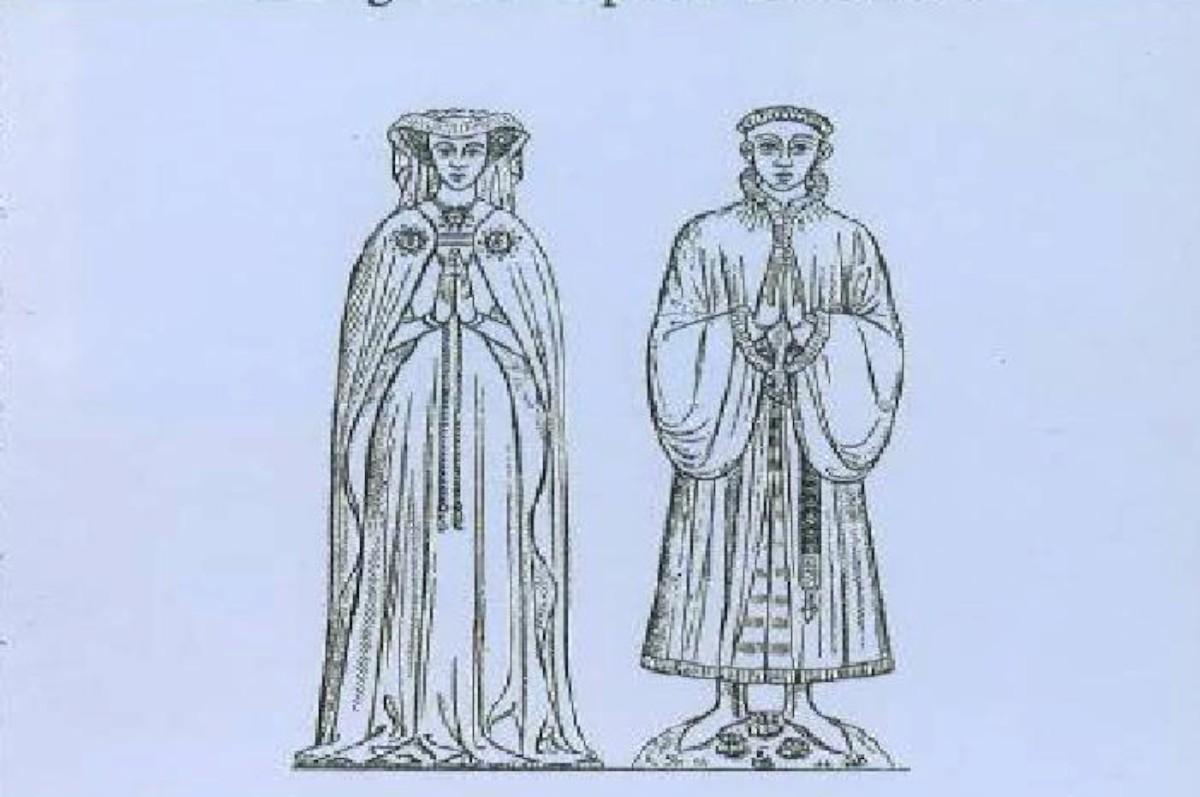

The pair lived in Down Hall – a riverside mansion, which Down Hall Road is named after – and their memorial brasses are among the many historic features of All Saints (popularly known as Kingston Parish Church).

And what of Queen Anne, whose golden statue has presided over Kingston Market Place since 1706?

Like many people, I had always thought of her as a relatively harmless fat fool, driven to drink by 17 pregnancies, the death at 11 of her sole surviving child, and her allegedly lesbian passion for the ruthless Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough.

As with Edward III, a meticulous historian and author has taught me otherwise.

In a 626-page biography, Queen Anne: The Politics of Passion ((Harper Press, £25), Anne Somerset sifts previously unpublished sources to show that under-rated Anne was, in fact, Britain’s most successful Stuart ruler, whose reign was marked by many triumphs, including union with Scotland.

Anne Somerset calls her “this most conscientious of rulers” whose life was so full of pain, care and sorrow that her physician deemed her death a mercy, knowing that “sleep was never more welcome to a weary traveller than death was to her.”

For more June Sampson features, visit http://www.surreycomet.co.uk/junesampson

Note: This feature was written before features editor June Sampson was involved in an accident.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here