The title convinced me it would be dry reading, but I was wrong.

The First 50 Years, A History of the Kingston upon Thames Society, is an unexpectedly gripping account of the topographical development of Kingston town centre between 1962 and 2012, and the part it played in making Kingston one of the most sought-after areas in the UK instead of the planning disaster that had originally been intended.

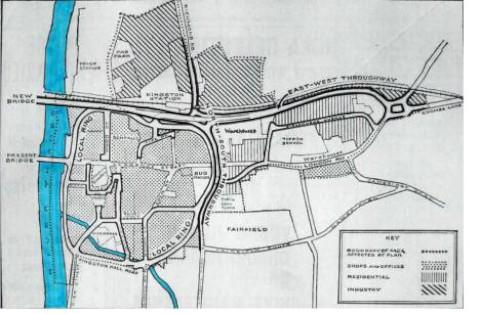

Imagine a traffic-packed ring road encircling the heart of the town centre and cutting it off from its greatest asset, the river.

Imagine a flyover towering over Wood Street to carry east-west through traffic to a new Thames crossing alongside the existing railway bridge.

Imagine Kingston without the continuous riverside walk that gives such pleasure to so many.

Those are just a few of the awful imaginings that could have become realities but for the Kingston upon Thames Society.

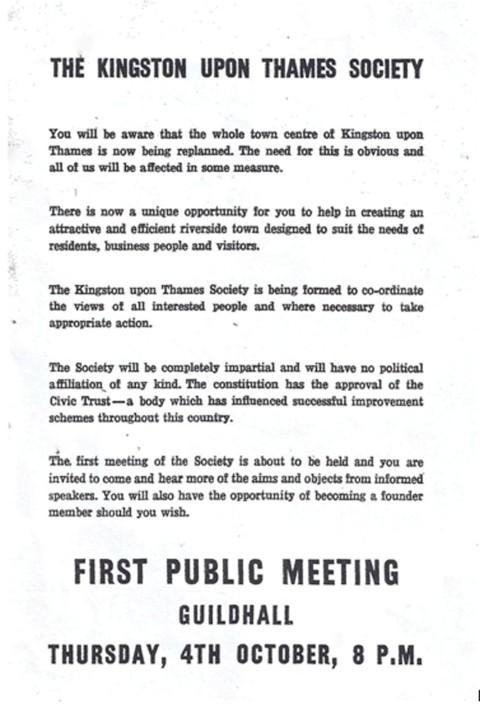

Indeed, they were already on the drawing board when the society was launched in 1962 by a group of architects appalled by the prospect of such drastic change being planned without public consultation.

The struggles that ensued and the hard-won victories eventually achieved are engagingly described in this new book by Michael Davison, a journalist and retired publisher’s editor, who joined the society in 1988 and was its chairman from 1994 to 1997.

One of his many surprising revelations is Kingston Council’s near-despotic attitude at that time.

Guildhall executives made it plain they saw the new society as a tiresome busybody, bent on meddling in planning affairs that were none of its business.

When the society eventually got them to agree to a meeting to discuss the so-called Kingston master plan (which would change the town centre almost beyond recognition) members were told any information revealed to them must remain strictly confidential.

In other words, there was no public right to know.

Later, when the society objected to the “brutalist” buildings planned for Brook Street, the borough planning officer, Kenneth Beer, replied “I have architects on my own staff who are well qualified to judge architectural quality” and that they had advised him the design was “acceptable and suited to the purpose and location”.

In 1975, informed of the society’s views on another development, Mr Beer told his committee he “did not think it worthwhile to include comments by lay people who could not appreciate the work of eminent experts”.

And when the society suggested joint working parties with council representatives to discuss important planning matters, they were told by the council’s chief executive, John Bishop, that “what may be a recreational activity to enthusiastic members of societies is simply extra work for staff”.

Not surprisingly, members of the society committee – several of whom were practising architects – took it hard that their efforts on behalf of the town were regarded as being undertaken solely for amusement.

The first aim of the society’s 83 founders was to oppose the master plan which, once revealed, horrified the bulk of public opinion.

But not all.

The Surrey Comet described it as a “a blueprint for progress... a brilliant scheme to reshape the town centre over the next 20 years and make it the most modern and efficient in the country”.

Undeterred, the society prepared its own amendments to the scheme. These rejected the riverside road and urged instead the opening up of the river frontage (a large portion of which was inaccessible to the public) with the continuous walk we have now.

In the years that followed, the society pressed for Market Place and Clarence Street to be pedestrianised (“impossible” said the planners) and in 1974 presented its own road plan.

This removed traffic from the town centre by a north-south relief road broadly similar to today’s Wheatfield Way.

That same year, the hated master plan was formally abandoned and when its successor was drawn up 10 years later there was no mention of a riverside road, nor of a second Thames bridge.

The society’s vision of a pedestrianised Clarence Street and Market Place, made possible by a north-south relief road, became a reality in 1989 and 2003 respectively.

And the final link in the riverside walkway was secured with the completion of Charter Quay in 2001.

As Michael Davison puts it, “the vision of the society’s founder members, and the persistence and patience of their successors, had finally been rewarded”.

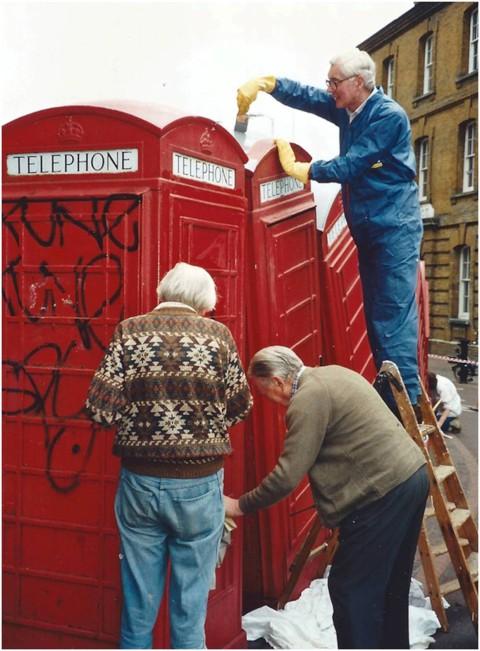

Meanwhile, the society had several other aims in its sights, such as saving historic town landmarks.

One such was 17 High Street, an elegant Queen Anne building that was home to the London Steak House at that time.

Thanks to the society’s pressure, the building was reprieved and though its interior was later rebuilt, its facade survives to this day.

Other buildings saved from demolition by the society’s efforts, or acting in conjunction with others, included Kingston Grammar School in London Road; Picton House, a riverside Georgian house in High Street; and Preston St Mary in Langley Avenue, Surbiton.

his, one of the most beautiful houses of its kind in the royal borough, was saved in a last-minute intervention after the demolition team had begun pulling it down in 1976.

As the years went by, the society brought influence to bear on a host of new initiatives, such as Charter Quay, where it was instrumental in getting the height of the apartment blocks reduced, and the Horsefair site, where the effect of the John Lewis development on the riverside was scaled down.

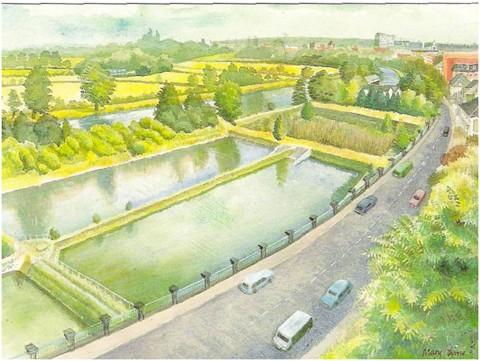

One of its current preoccupations is the development of the filter beds in Portsmouth Road.

Initially it strongly opposed the multi-storey buildings proposed for the site.

However, a new scheme that would retain one filter bed as a nature reserve, accommodate 64 “floating homes” on the others, and provide a marina, public access and a new stretch of riverside, has won the society’s support.

To quote its current chairman, Jennifer Butterworth: “The scheme seems to us to present a better solution than any other likely to be made in the future for a site that is a terrible eyesore and without public access.”

This change of heart has, understandably, disappointed those who have been campaigning since 1996 to have the site listed as Metropolitan Open Land.

The society’s host of other activities, such as management of the 16th century Coombe Conduit, co-ordinating the borough’s heritage open days programme, townscape awards for new buildings of distinction, visits to buildings and towns of interest and monthly public meetings with guest speakers, are all detailed in this book, which has been published by the society to mark its golden anniversary, and was launched at its annual general meeting this week.

It costs £5, and can be bought from Kingston Museum in Wheatfield Way or the history room in the North Kingston Centre in Richmond Road.

It can also be ordered from Michael Davison at 5 St Alban’s Road, Kingston KT2 5HQ, for £7, including postage and packing.

Perhaps its most salient message is what can be done by the determined efforts of people who truly care about their environment to achieve what they, rather than unaccountable planners, want – to see in their town.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel